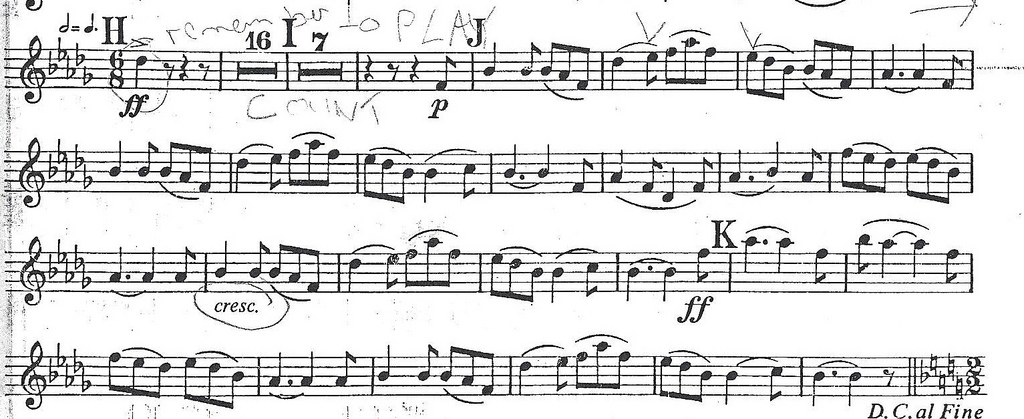

It’s been a busy week - back to back rehearsals for the Wind Band (loving the Holst), String Band (Handel on the concertina is like yoga), Folk Band (Jenn Butterworth’s guitar playing is phenomenal) and Choir (an unexpected addiction - all that breathing is amazing for a flute player), as well as theory and a private lesson.

Behind the scenes, though, I’ve discovered another world - music on the 21 bus! It takes well over an hour to get from Portobello to Stevenson College. There are other bus routes that may be quicker but involve changing in town, but the timings of the 21 have worked better this week and the 21 has the added advantage of providing a long unbroken period of listening. During our first week, Tommy Composer urged all of us to listen to music for at least three hours a week, and I’ve taken that to heart.

Access to music has changed fundamentally since I was younger. As a teenager, I listened to the local radio and occasionally bought an LP, but records were too expensive to experiment with. The music of the 70’s - 80’s pretty much passed me by - I listened to the radio on the way to work, but it was a busy time, too busy to spend time just listening, and by the time the 90’s came along, the music I heard was likely to be “The Wheels on the Bus” or the theme song from Spot the Dog. Since then, though, access to music of all kinds has been revolutionised with ipods, mp3‘s, myspace, spotify, itunes, to name only a few.

What determines what we really like, or what’s okay but doesn’t make us want to listen to again and again? I've subscribed to Spotify and am trying to find out. Besides having access to all the music in the Spotify library, there is also a "Related Artists" feature which connects listeners to similar types of music.

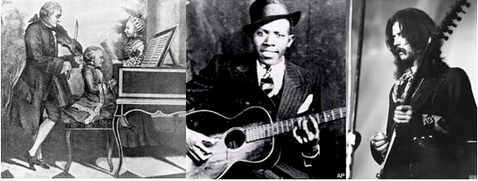

I started out in September listening to blues and pop - Honeboy Edwards, Eric Clapton, Ian Anderson, Jethro Tull, Led Zeppeling and the Rolling Stones. Nice...interesting... but doesn’t really rock my world.

Alasdair Fraser’s two new cds with Natalia Haas contain some nice sets, but only Rob Fraser’s Welcome to San Francisco gives me the shivers every time I hear it. I don’t know why, but for me beautiful waltzes are the ultimate pleasure, and I plan to be playing this tune myself soon.

For my flute private lessons, I’ve been listening to Chris Norman’s wooden flute playing across the range of his cd’s. Keeping his sound in my mind is helping my own playing, but the style of his traditional tune playing is not what I’m trying to find in my playing. So that always brings back my endless internal discussion about what I want my own “voice” to be.

Habbadam’s new cd, Still Young, is as lovely as I hoped it would be. Habbadam is a young Danish trio, from Bornholm, an island closer to Sweden than Denmark. Their first cd was a delightful collection of 18th century tunes, with a familiarity to traditional Scottish music of the same period, and the new cd continues in this vein with the addition of some new tunes.

I’ve dipped my toe into Valkyrien Allstarts, Paolo Nutini, Bob Dylan, Suzanne Vega and Chuck Berry (they took me back), Vivienne Long, old John Martyn songs, The Shins, Philip Glass and Michael Nyman, among others. I may be back to listen to some of them, but none have made it to my “top priority listening” list.

The pleasures have turned out to be Ray LaMontagne, Catie Curtis, Ane Brun, Damien Rice, Kris Delmhorst, and my “guiltiest” continuing pleasure over the past year, Antje Duvekot.

Behind the scenes, though, I’ve discovered another world - music on the 21 bus! It takes well over an hour to get from Portobello to Stevenson College. There are other bus routes that may be quicker but involve changing in town, but the timings of the 21 have worked better this week and the 21 has the added advantage of providing a long unbroken period of listening. During our first week, Tommy Composer urged all of us to listen to music for at least three hours a week, and I’ve taken that to heart.

Access to music has changed fundamentally since I was younger. As a teenager, I listened to the local radio and occasionally bought an LP, but records were too expensive to experiment with. The music of the 70’s - 80’s pretty much passed me by - I listened to the radio on the way to work, but it was a busy time, too busy to spend time just listening, and by the time the 90’s came along, the music I heard was likely to be “The Wheels on the Bus” or the theme song from Spot the Dog. Since then, though, access to music of all kinds has been revolutionised with ipods, mp3‘s, myspace, spotify, itunes, to name only a few.

What determines what we really like, or what’s okay but doesn’t make us want to listen to again and again? I've subscribed to Spotify and am trying to find out. Besides having access to all the music in the Spotify library, there is also a "Related Artists" feature which connects listeners to similar types of music.

I started out in September listening to blues and pop - Honeboy Edwards, Eric Clapton, Ian Anderson, Jethro Tull, Led Zeppeling and the Rolling Stones. Nice...interesting... but doesn’t really rock my world.

Alasdair Fraser’s two new cds with Natalia Haas contain some nice sets, but only Rob Fraser’s Welcome to San Francisco gives me the shivers every time I hear it. I don’t know why, but for me beautiful waltzes are the ultimate pleasure, and I plan to be playing this tune myself soon.

For my flute private lessons, I’ve been listening to Chris Norman’s wooden flute playing across the range of his cd’s. Keeping his sound in my mind is helping my own playing, but the style of his traditional tune playing is not what I’m trying to find in my playing. So that always brings back my endless internal discussion about what I want my own “voice” to be.

Habbadam’s new cd, Still Young, is as lovely as I hoped it would be. Habbadam is a young Danish trio, from Bornholm, an island closer to Sweden than Denmark. Their first cd was a delightful collection of 18th century tunes, with a familiarity to traditional Scottish music of the same period, and the new cd continues in this vein with the addition of some new tunes.

I’ve dipped my toe into Valkyrien Allstarts, Paolo Nutini, Bob Dylan, Suzanne Vega and Chuck Berry (they took me back), Vivienne Long, old John Martyn songs, The Shins, Philip Glass and Michael Nyman, among others. I may be back to listen to some of them, but none have made it to my “top priority listening” list.

The pleasures have turned out to be Ray LaMontagne, Catie Curtis, Ane Brun, Damien Rice, Kris Delmhorst, and my “guiltiest” continuing pleasure over the past year, Antje Duvekot.

I stumbled across Antje Duvekot, a Dutch-American folk singer, after reading a review of her last cd, The Near Demise of the Highwire Dancer, in one of the Sunday papers. Since then, I’ve acquired all of her previous recordings - she has a unique voice, her songs are personal and they remind me of growing up in the midwest, in a good way.

Last summer, Antje notified everyone on her emailing list of her www.Kickstarter.com fundraising project for a new cd. Making a cd is expensive, and often beyond the budget of talented but not yet megastar musicians, (and really, how many folk singer songwriters ever become megastars?). Kickstarter.com is an innovative website initiative that provides musicians, artists, and entrepreurs with the opportunity to fundraise for new ventures. Antje Duvekot offered supporters options, from just giving $1, donating $25.00 (£15) and receiving a copy of the cd as soon as it’s available by post (which I and 188 other backers signed up for), through donating $5,500.00 and receiving a cd and a private acoustic concert in your own house (two backers bought that option). Her goal was to raise $20,000 by 29 July - in fact, she raised $33,018, and the cd is due out by Christmas!

Kickstarter ... yet another great opportunity from the internet!

Last summer, Antje notified everyone on her emailing list of her www.Kickstarter.com fundraising project for a new cd. Making a cd is expensive, and often beyond the budget of talented but not yet megastar musicians, (and really, how many folk singer songwriters ever become megastars?). Kickstarter.com is an innovative website initiative that provides musicians, artists, and entrepreurs with the opportunity to fundraise for new ventures. Antje Duvekot offered supporters options, from just giving $1, donating $25.00 (£15) and receiving a copy of the cd as soon as it’s available by post (which I and 188 other backers signed up for), through donating $5,500.00 and receiving a cd and a private acoustic concert in your own house (two backers bought that option). Her goal was to raise $20,000 by 29 July - in fact, she raised $33,018, and the cd is due out by Christmas!

Kickstarter ... yet another great opportunity from the internet!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed