It’s been a weekend of astonishing music from across the North Sea and Iceland. Northern Streams, now in its ninth year, never fails to inspire me with the diverse and excellent music showcased. What did surprise me was the different paths that the Swedish and Norwegians musicians have taken to arrive in their music.

Melodeon player Rannveig Djønne’s performance with singer and hardanger player, Annlaug Borsheim, in Saturday evening’s concert was an example of sheer beauty in simplicity. At Saturday afternoon’s last workshop, Rannveig Djønne was disarmingly unassuming. She commented on her lack of musical training, but added that she did know the names of the harmony buttons on her three differently tuned melodeons! The first Norwegian to play her country’s traditional music on the melodeon, she recounted how she attended the traditional music college some 29 years ago. And then she played Bambas, a lullaby written for her oldest niece (and told a story about writing a more fiery tune for her younger niece, a “little viking”). We were all blown away by the sheer beauty, of the tune, of her playing, of the arrangement. It was the most beautiful melodeon playing I have ever heard, her use of the fully extended bellows was amazing. Click on the picture to have a listen - her music will stay with me forever.

Similarly, singer and hardanger player, Lajla Buer Storli, told us in her Saturday morning workshop, that she doesn’t read music, and has minimal music theory. To learn some of the oldest Norwegian tunes on manuscript, her husband plays them from the sheet music, and she then learns them by ear from him. In her workshop, she taught us an old Halling and a waltz that she believed may have come from the UK, by way of the tourist boats that visited Norway, resulting in cross-cultural music influences. Ditte Mortensen, fiddle player with Danish Bornholm-based band, Habbadam, has previously expressed a similar belief in the way that Bornholm’s eighteenth century music seems to have a link with Scottish baroque music.

Fiddle player Emma Reid and saxophonist Daniel (formerly Carlsson) Reid have come to their music from more “conventional” routes. I first met Daniel at Northern Streams three years ago, when he performed as part of the band, One Fine Day, and co-taught a flute workshop with the scottish wooden flute player, Calum Stewart. This year he performed with his wife Emma who was born in Northumberland to a Swedish mother and moved to Sweden 12 years ago. The combination of fiddle and saxophone is unusual but works extremely well. In the afternoon workshop, the Emma taught us a lovely slang polska, and then Daniel demonstrated modal drones and rhythmic riffs as effective harmonies. Daniel has a broad background in classical music as well as jazz and folk, and teaches at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm while Emma graduated from Newcastle University and then the Royal College of Music in Stockholm. Their music is firmly rooted in the Swedish tradition, imbued with rhythm but at the same time articulate and with well-honed technique.

For me, the stars of Friday night’s concert were Karin Ericsson Back and Maria Misgeld. Singing acapella. Two of three members of the band Irmelin, their harmonies and canons were entrancing. They committed wholly to the music and were a joy hear.

All of these Nordic musicians are so generous with their time and their art. They invited us whole-heartedly into their music, sharing with us as they themselves have had other traditions share with them. Shetland’s music is acknowledged as a continuing influence, as are the other nordic countries. The only disappointing thing about Northern Streams 2012 was the paucity of the audience in both the concerts and the workshops. Northern Streams is such a great opportunity to expand musical horizons. Why are so few of us interested in engaging with our northern neighbours...

Recently, I’ve been working on Telemann’s Concerto in E minor for Two Flutes with Basso Continuo TWV 53: e2, Burn’s Highland Mary, a set of contemporary strathspeys ending with a jig, a set of polkas and Handel’s Flute Sonata in F for my recital (more of that in another blog).

We’ve just come to the end of the third performance block, and what a joy it’s been making music together, although music is such a conundrum. After rehearsing the Telemann, in which I played Concertante (solo) flute 2, I come away all serene and think to myself that I can play the flute. After a wind band rehearsal of Copland’s Salon Mexico, where the first flute part is at the absolute top of the range and I can hardly play it (too much shrieking!), I come away wondering whether I will ever be able to play the flute. It’s a balance - playing baroque music is intangibly joyful while mastering something like the Copland will be an achievement. I know that if all the music I played was easy, it wouldn’t be an enduring pleasure and it wouldn’t keep my attention for a lifetime.

It’s not surprising that Telemann was so prolific. Born in 1681, he lived until he was 86, dying in 1767. The Oxford Music dictionary observes that “He remained at the forefront of musical innovation throughout his career, and was an important link between the late Baroque and early Classical styles. He also contributed significantly to Germany’s concert life and the fields of music publishing, music education and theory.” He composed over 1000 works, of which at least 125 were concertos. Many of these were “tafelmusik”, smaller scale pieces designed for domestic music-making. I would have like to know more about when and why Telemann composed this work. I have been unable to find information specific to the concerto we played, but it appears to have been composed around 1720 - 30. Have a listen - (I've removed the clapping between movements, and normalised the recording in audacity).

Concerto Grosso in E minor for Two Flutes and Bassoon - Stevenson College String Group:

In a completely different genre, some utterly simple tunes like Highland Mary are so beautiful in themselves that they transcend everything else. Our arrangement, which weaves instrumental interludes around the solo voice, never failed to create a shiver down my spine - so lovely.

Highland Mary - Stevenson College Trad Band:

While I’m looking forward to enjoying the Easter holidays, I have already started having nightmares about my recital and there’s so much work to be done for theory! Onward... and onward.

The BBC has outdone itself recently with it’s classical musicology programming. Simon Russell Beale’s “Symphony” series was shown at the end of 2011, and Charles Hazlewood’s “Birth of British Music” , originally produced in 2009,is being shown again on BBC 4. This series looks at four 17C - 19C composers, Purcell, Handel, Haydn and Mendelssohn. Perhaps the irony of the German view of Britain as the “the land without music”* is not lost in the fact that in “The Birth of British”, only Purcell was actually British.

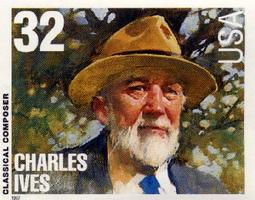

I only managed to catch the “Revolution and Rebirth” episode of Symphony, in which Beale looked at the symphonic works of Shostakovich, Ives and Copland. Wonderful music especially, for me, because all three composers incorporate their sense of culture and country into their music. I first heard Charles Ives’ Fourth of July (from the Holidays Symphony) when I was in secondary school, and I remember laughing out loud at the accuracy of the portrayal of one of America’s most “sacred” holidays. I listened to it again today, and while it starts darker than I remember, the later section still makes me laugh.

We were very fortunate, at Stevenson College in the early part of February, to have the opportunity to hear Tim Paxton (cello) and Simon Coverdale (piano) perform a Shostakovich cello sonata. In his introduction, Paxton referred to Shostakovich’s ability to be "everything for anyone", a technique that enabled him to surviving the totalitarian regime under which he spent his entire life. Much of his work was double-edged and ironic, embodying the requirement to be a good proletarian composer, his own struggle for identity and his alienation from the regime. The cello sonata was a very dark work, such despair, and though the mood lightened somewhat by the end, the music held no assurance that everything would be all right.

While the concept of the ”land without music” looks at the dearth of formal, classical composers in Britain, it also reveals a snobbish ignorance of the plethora of vernacular music throughout the British Isles.

Ordinary people have enjoyed vernacular music all over the world since time in memoriam. Scotland, Ireland, England and the Nordic countries, in particular, have rich folk musical traditions which have been woven into the music of formal composers such as Handel, Vaughan Williams, Sibelius and Grieg. Others, such as Mahler and Shostakovich, have written big, gorgeous works incorporating folk melodies at the heart of the music. Even in young countries like Canada and the United States, the melodies of the developing communities have been captured by such as Charles Ives and Aaron Copeland.

In all things, labels can be used either to gather together, or to separate. It’s not uncommon today to hear classical musicians say, “I’m not a folkie”, with the implication that folk music is something too informal or too primitive to have value. Folk music is about melody - usually simple but extraordinarily beautiful melodies. Those folk melodies have found their way into bigger, more complex music - and where would that music be without them?

* "Das Land ohne Musik" - “The earliest source yet given for this rather persistent German generalisation – for the French, I believe, have never concerned themselves much with English musicality at all – is Carl Engel's book of 1866, which Oskar Adolf Hermann Schmitz in his Das Land ohne Musik : Englische Gesellschaftsprobleme quotes as a reference. In fact the prejudice held by the Germans in this respect must be adjudged of rather earlier origin than even that.” http://www.musicweb-international.com/dasland.htm

I was watching the BBC’s Imagine programme, Simon and Garfunkel - The Harmony Game recently. Well worth watching for the discussion of how the album, Bridge Over Troubled Water, was recorded and the musical influences that went into it. The thing that stood out for me the most, however, was the furore that was caused by their “humanistic” ethos during the making of Songs of America, a CBS TV special about the duo, filmed in 1969 and originally funded by one of the major telephone companies. Apparently millions of Americans turned to a different channel because of their unhappiness with political content of the show. Songs of America was criticized for being biased towards the Democrats, because it referred to the assassinations of John and Bobby Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, while Coretta King’s comments on child poverty were dubbed out. Yet, the reaction to the programme makes sense if you look at the social identity of the two. SImon and Garfunkel were two middle-class jewish boys from New York, key players in the American folk music scene of 60’s - 70’s. They were listened to by scores of other white, middle class, educated liberal young people.

After the Revolutionary and Civil wars, Americans are used to referring to their society as “classless”, and yet social background has always played a huge role in the music that people listen to. The Blues grew out of destitution of ex-slaves in the south. Jazz had it’s roots among African Americans in more urban areas, influenced by the blues.

Folk music, as played by Joan Baez, Judy Collins and James Taylor from the late 1960’s, was embraced by the anti-Vietnam war movement, and embraced the end of segregation by supporting the civil rights movement. You wouldn’t have found many white collar workers or Ku Klux Klan members listening to folk, which they viewed as “pinko” (leaning to the left) music.

Similary, country music grew out of the folk instruments that had been brought to areas like the Appalachian mountains by poor white European immigrants, and spread through southern and south western white communities. You didn’t find many Country Western musicians in Boston or Woodstock in the 70’s.

Numerous research projects have looked at the sociology of music: “..the relationship of youth to music was found to differ significantly along a number of dimensions, particularly those of social class, gender, and ethnicity.”* Numerous books have been written on the subject: “The music industry daily invents and redesigns labels to market musical products as new and / or authentic.”**

So how do you know what genre a particular musician belongs to?

You can look at the classifications of music shops such as itunes, amazon or play.com but that may tell you as much about the business goals of those websites as it does about the musicians.

You can look at the music’s harmonic structures, but there’s a big overlap between folk, country and rock. You can look at the social strata of the people who listen. You can look at the genre of the radio stations that play the music.

You can ask the musicians themselves for a more valid definition. Canadian Neil Young’s early music leaned towards folk, he had a period of anti-establishment protesting embodied in the cd Living with War Today, but some of his later work he himself refers to as country rock. Or you could ask the listeners what genre they would given a particular musician.

Over time, people’s perceptions of genre change and the genre themselves are influenced by other musical influences. Jazz turns white and country turns popular.

Does it really matter, anyway? Well, I can think of more than a few Scottish traditional musicians who would object to their music being referred to as Morris tunes - even though there’s a large overlap between Scottish, English and Irish music. I just think you have to be aware of the power of cultural insensitivity... and try to avoid it, if you can.

*/www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/DATABASES/MIE/Part2_chapter03.shtml

**Fabian Holt, Genre in Popular Music. Also Edwards, Leigh H., Johnny Cash and the Paradox of American Identity, and Eyerman, Ron, Music and Social Movements: Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century.

Another year, a few more grey hairs and the opportunity to ponder good intentions, and sort out bad decisions.

I guess my main goal for the year is to survive the Degree Foundation Music course I’m on, and hopefully do well!?! I kind of leaped at the opportunity to do this music course, and with hindsight, I think I thought it would be a walk in the park. We’d arrive on the first day, unpack instruments, and spend 10 months playing tunes and generally having a chilled time. I could not have been more mistaken.

Unbeknownst to me, the course includes a rigorous theory component, and when I arrived my ignorance was very noticeable to me. With 3 weekly theory classes since September, music theory is being transformed before my eyes from something rather mysterious and scary into a surprisingly comforting numeric logic. I understand modes! I love scale spellings, and while I might not be able to get my fingers round all of them, I love the pattern of major, minor and “flat 5” 7 chords! Last September, I didn’t see any need for me to focus on Classical Music Theory, and negotiated an additional more advanced Pop Theory class instead. Since dabbling in classical music, and taking up the silver flute, I have come to regret that decision, and have now added an additional Classical Music Theory class to my capacious theory load. Theory is indeed a beautiful art in itself, let alone an essential means of translating musical intentions into reality.

Another goal for 2012 is to further develop my technique on all three instruments: wooden flute, english concertina and silver flute.

I’m currently playing three Canadian waltzes on the wooden flute, involving a lot of playing at the very top of the flute, a territory rarely ventured into by most traditional flute players. A lot of my focus right now is in improving my third octave sound. I’m finding that playing harmonics on both flutes and working my embouchure at the top of the silver flute’s range is helping, but it’s going to take time to make new habits.

I’m also working my way through Trevor Wye’s Practice Books 1 - 5 Omnibus, full of finger and mouth agility exercises. I’m thinking about the colour of tone, and whether all the notes in a scale can have the same colour. The exercises are strangely comforting to play, akin to the pleasures of learning theory.

Now that we’ve moved on to Country music as a style for improvising, I am turning my concertina focus onto playing chord accompaniment. I have always been primarily a melody player, although in the band I do play concertina chords for a couple of sets. While I find it relatively easy to learn tunes by ear, I find it more difficult to spontaneously play chords for tunes that I haven’t worked up, and that’s an area I hope to develop.

We’ve had several discussions, in class, on practice routines with the suggestion that we develop a fixed practice schedule. I find that a fixed anything quickly becomes something that I fail at and resent. Flexibility and focus on time-critical goals and weaker areas works better for me, evidenced by my progress. Every day I review (mentally and on paper) what I need to do. Then I prioritize the work against deadlines (blog deadline dates, composition deadlines, homework assignments, private lesson dates). It can be hard to find the time to practice three instruments every day, but I do try to play both flutes six days a week, and fit the concertina in at least a few times each week. I regularly record myself, listen back and then work until the recordings reflect what I’m trying to achieve.

As part of my course, I’m encouraged to develop networks, create new contacts, and market myself as a musician. If you’re reading this blog, you’ve already come across one of my self-promotional tactics! Playing in trad sessions is often a great way to make face-to-face contacts, while there are many online opportunities to promote oneself, including Facebook, Twitter, chiffandfipple.com flute forum, concertina.net and linkedin.com . I’ve also included my website on stumbleupon.com , which randomly generates website suggestions to members based on membership preferences. It must all be working, as in the past few months the hits on my website have increased, I’ve had an email from a new concertina player looking for information and another beginner looking for a lesson, I’ve received information about the Scottish Flute Summer School from a new contact, and I’ve had a request to play at a gig next year.

So how will I address these good intentions and goals? Through hard work, continual self-assessment and heaps of practice. Lots of sweat, a few tears but hopefully not much bleeding, except from my ego.

Onward and upward in 2012.

PS You may remember me mentioning Antje Duvekot’s Kickstarter project, in a previous blog? The cd, New Siberia, arrived in the post last week, and it’s a cracker! She emailed me to thank me for the mention in my blog. The internet is the biggest connection for us all...

Music has always been an important part of small Scottish communities. In the long, dark of winter, villages came together to entertain each other in community ceilidhs. On Easdale Island, the Ne’er’s Day ceildh is a thriving tradition, alongside first footing into the early hours of Hogmanay, the New Year’s Day football match and the ocean swim (definitely not for the delicate)!

This year, the first since I started playing the silver flute again, Zoe (a bassoon-playing friend) and I decided to attempt the first movement, Allegro Commodo, from Beethoven’s First Duo (originally for clarinet and bassoon) in C major. We first read through the music the day before for a short rehearsal, and had one more short rehearsal on New Year’s Day. We probably played it better in rehearsal, but in the ceilidh, despite mistakes we managed to keep going and got to the end, not exactly together but close!

The flute and bassoon is an unexpectedly delightful combination, and it was such a joy to play this kind of music as a duet. I’m finding it quite ironic that the Traditional Music Performance DFM course has led me back to classical music!

It’s blowing a gale out today with sleet and hail - we may be marooned for a while, but at least we’ll be entertained.

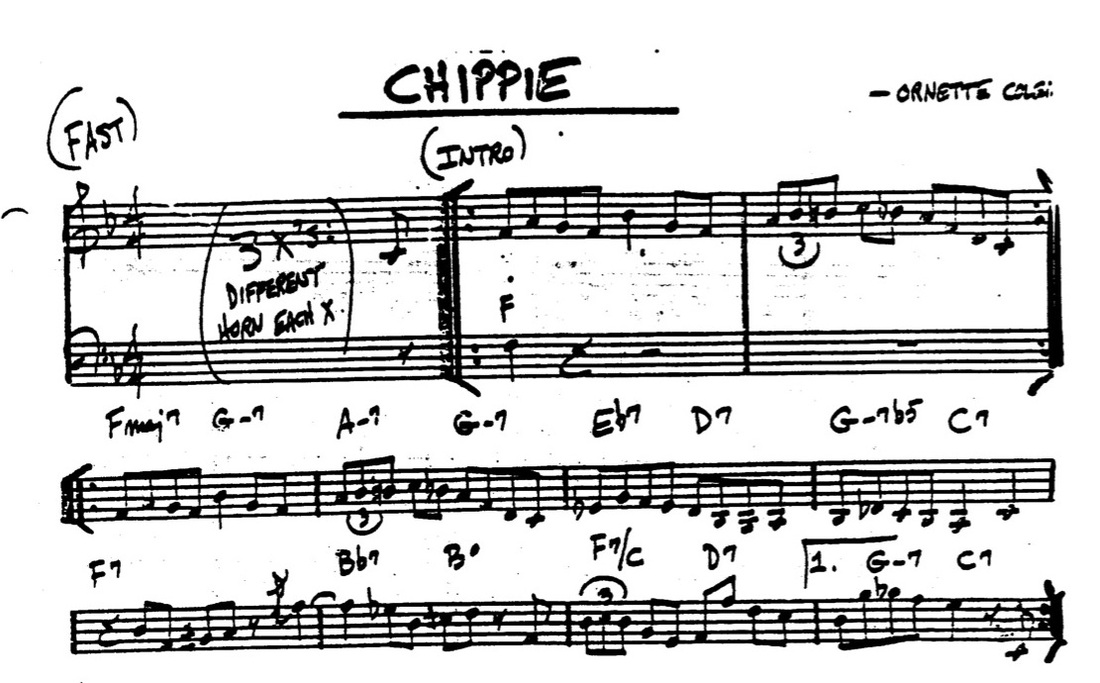

While I may not be a jazz aficionado, I am interested in learning how to analyze a jazz lead sheet, comprised of the “head” (main melody) and “chorus” (chord sequence, once through).

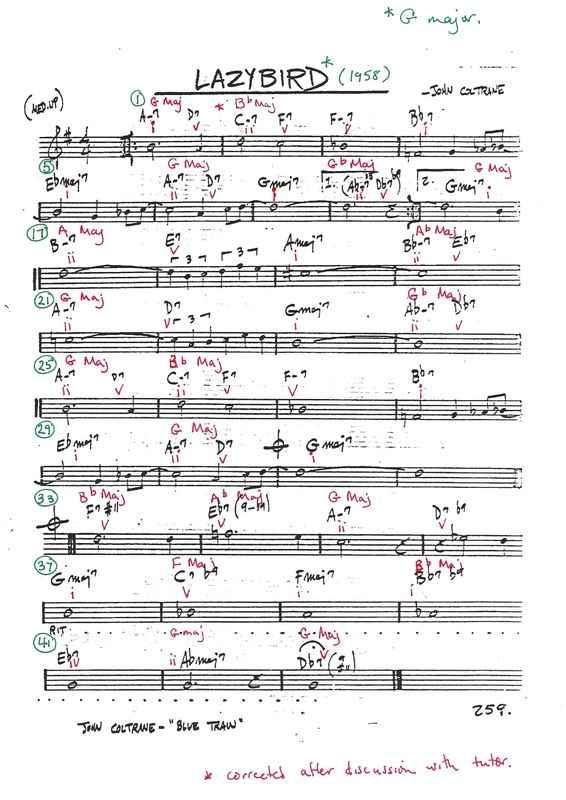

I’m fascinated by the way jazz musicians create chord sequences first, and then fit melodies and improvisation to the harmony. As a traditional musician, I work in the opposite way, composing a melody first, and then just playing it with other musicians, hoping the guitar player will be able to figure something out! Surprisingly, some of the jazz melodies are really lovely - and would sound almost like traditional music if played slowly, with a different harmonic base. See the opening melody in Ornette Coleman’s tune “Chippie” below: Analyzing a Jazz Song - John Coltrane's Lazy Bird John Coltrane was born in Georgia in 1926, the same year as Miles Davis, and like Davis and Honeyboy Edwards, he was the grandson of slaves. However, his maternal grandfather, Reverend William Wilson Blair* had become a religious and political leader in his community, and Coltrane was raised in a religious home. He attended a High School for African American students opened by his grandfather, and then went on to music school. He was a multi-instrumentalist, playing saxophones, horns and even the flute. In 1945 he enlisted in the US Navy, and was stationed in Hawaii where he played in the Navy jazz band. He was part of Miles Davis’ band for Kind of Blue, and is quoted on johncoltrane.com as saying”Miles music gave me plenty of freedom”. 1958, John Coltrane released his Blue Train album on the Blue Note label. It is considered to have been his favourite album. Blue Train was post bebop but pre-free jazz - I found numerous references to the style as “hard bop”. Lazy Bird, the jazz song I’m going to try and analyze below, was the last track on Side 2 of the LP, was written by John Coltrane himself, and lasted 7 minutes.

Lazy Bird is in 4/4 in the key of Gmajor. The A-part is 16 bars long in total, made up of 7 bars that repeat, with different 1-bar tags for the first and second endings.

The B-part is 16 bars long, made up of a 4-bar melodic figure that is repeated a whole tone lower (8 bars), a 3-bar melodic phrase, and then a small ascending [crotchet / quaver quaver / minim] figure used three times and including a [tied quaver minim] that crosses over a bar line.

The harmonic structure is:

A-part:

Bar 1: Chord sequence is ii v of G major

*Bar 2 - 5: Transition to Bflat major with backdoor sequence ii v i

Bar 6 - 7: The key is back to Gmajor ii v i

Bar 8 - 1st ending is ii v of Gflat major with complex chords Aflat minor13 and Dflat7flat9 / 2nd ending is i of G

B-part:

Bars 17 - 19: The key has changed to Amajor ii v i

Bars 20: Change of colour using the ii v of Aflat major

Bars 21 - 23: Back to the root of Gmajor in ii v i

Bar 24: Change of colour as in bar 20 using the ii v of G flat major

Bars 25 - 32: Identical harmonic structure to Bars 1 - 8 of A-part, a very lazy bird indeed.

Coda:

I’m assuming the cross-hatched circle symbol is a a coda played before the end. If the final chord is the Dflat 7 (9 # 11), then the song finishes on a v chord, but if the final G chord is played after the end of the previous chord, then the song ends on a v i cadence.

The chords in the coda are more complex, including a #11, 9 and flat 9’s, and a 9 #11 . I don’t have the experience to really understand why these chords have been included, but I guess they add extra colour to the coda improvisation.

Bars 33 - 34: Descending key sequence: v of Bflat / v of Aflat

Bars 35 - 37: Descends back to G major ii v i sequence

Bars 38 - 42: Continues to descend: v i of Fmajor / v of Eflat major / v of Aflat major. However, Eflat7 chord in bar 41 could be a substitute for an Eflat major7 chord which would make a i iv sequence in Eflat

Bar 43: finishes with v of Gmajor

*corrected after discussions with teacher This is the first piece of music I’ve ever analyzed in this way, and no doubt there are better methods or language in which to do this. Lazy Bird opens with a simple melody, but It’s been interesting to find the patterns, both melodic and harmonic, which I've been unaware of just listening to the music. I’ve been surprised by the number of chords in flat keys in a song that’s in a sharp key. Analyzing the song gives me a glimmer of understanding, where previously bebop and free jazz have been pretty much impenetrable to me. It would be interesting to analyze the improvised solos in the same way, but that would be even more time-consuming and a topic for another blog (in another lifetime?!?).

*John Coltrane and Black America’s Quest for Freedom - Spirituality and the Music, edited by Leonard L. Brown, Oxford University Press, 2010. p. 146

I am finding jazz a challenge, although there have been some surprises. I thought I would prefer to move forward in the jazz timeline to get away from all the racism African American musicians experienced at least before the 1970‘s. I find, however, that listening to a lot of contemporary jazz makes me feel uneasy or even downright uncomfortable. I listened to a Christian Scott youtube clip, and while the trumpet and piano playing was fine, (although perhaps not as lovely a tone or as expressive as Miles Davis), I found the drummer’s playing completely inscrutable - no pulse, no evident rhythm, just what seemed like a cacophonous background. I just don’t get it and I just don’t enjoy it.

Jazz doesn’t seem to have a specific definition, but ranges over lots of different styles, including: Bebop, Dixieland, Cool, Jazz Funk, Modal, Acid and Cool. Oxford Music Online defines jazz as resulting “from three developments: the addition of blues rhythms and pitch inflections to rags and other popular song and dance forms; the undergirding of rags and other two-beat forms with a 4/4 ground beat; and the uneven playing of eighth-notes.” The Kennedy Center (NYC) website defines jazz as a feeling of triplets behind a basic beat giving a swingy style to the music, improvisation, reliance on sycopation and an AABA song form. ( Oxford Music Online and www.kennedy-center.org)

It’s hard to define what I look for in music, and to specify what I like. Unfortunately, it’s been easy to find jazz that I don’t enjoy. The list of who I reallydon’t enjoy includes Steven Coleman, Lydia Lynch, Keith Parker, Charles Mingus, Johnny Hammond Smith and Stefan Grupelli. The list of who I just feel unengaged by includes Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Thelonius Monk. (spotify.app) I guess that what I look for in music is a structure, a melodic framework with repetitions that are mostly predictable, sometimes unexpected, but develop in an understandable or even comfortable way. Most traditional music has this sort of pattern. For example, 2/4 pipe marches are mainly in four parts, AABBCCDD or often AABBCCDA, and are usually played twice. Polskas and waltzes are usually in AABB or AABA form where the initial melody of the A part becomes the closing phrase of the B part providing a simple musical resolution. I can whistle along to this sort of music and be part of it in a way that I find unaccessible in the jazz of the musicians mentioned above.

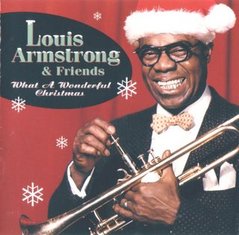

I have been stunned to discover, however, that Louis Armstrong’s songs performed with Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby or Duke Ellington are classed as jazz. I have been equally stunned to discover that I really enjoy hearing these songs. They take me back a long way. They have beautiful melodies, optimistic lyrics and gentle improvisations providing a varied texture to the music. It’s interesting to hear younger musicians like Michael Buble and Jamie Cullum harking back to this period and both reproducing these songs, and writing new music in this style. On the one hand, I find myself feeling entirely politically incorrect in enjoying listening to a man who was the grandson of a slave sing, in his rich voice, What a Wonderful World. On the other hand, I find the voice, words and music moving, beautiful and so optimistic, a nice change to the doom and gloom that surrounds us. Louis Armstrong was a huge success in America, although he was considered by some of his fellow African Americans to be an Uncle Tom. He was welcomed in hotels and venues that were closed to most other black people. He was revered by the same white America that ordered his fellow blacks to sit at the back of the bus because of their colour.

Much of the world’s music has been born out of suffering, politicization or denial: Mahler’s denial of his jewish background, Shostakovich's’ role as the propaganda voice of the Soviet Union and subsequent denouncement, Jerusalem as an expression of the English colonial regime, just to cite a very few examples. I have to believe that music transcends the circumstances under which it was created, or else deny myself huge swathes of music that I enjoy.

Despite the incongruity of his life, Louis Armstrong’s success may have been a tour de force against segregation and racism, working within the system rather than outside as some, like Malcolm X, prescribed. However, much as I enjoy listening to Frank Sinatra sing a jazz version of Chestnuts Roasting in an Open Fire, it does feel that this sort of jazz is typical of the way in which the US dilutes other people’s cultures, a sort of Tex-Mex version of jazz. I’ll continue to listen to these old gems but I am mindful that the white American popularization of an essentially black art form is a form of the American cultural imperialism that threatens world cultures today. At the other end of the timeline, I have discovered Nu Jazz and Norwegian Jazz, and am so enjoying listening to the beautiful melodies of musicians like Bugge Wesseltoft and the Esbjorn Svensson Trio ((est) www.myspace.com/esbjornsvenssontrio).

Have a listen to est’s Believe Beleft Below (Seven Days of Falling) or Bugge Wesseltoft’s Mitt Hjerte Alltid Vanker (It’s Snowing on My Piano cd, 1997). In Bugge’s lattest cd, Kammermusik (Wesseltoft Schwarz Duo cd, 2011, www.buggeandhenrik.com) he combines jazz elements (some generated by Schwarz on his laptop) with melodic piano lines that would have been at home in a completely different age. Nu Jazz’s pensive and lyrical playing in no way resembles the music of Miles Davis or Dizzy Gillespie, and yet, it all appears to be jazz.

That’s hard to understand.

So what are your views on jazz and the politicisation of music? Feel free to comment below!STOP PRESS - I've just stumbled across an amazing Rick Stein programme on the blues! Very interesting, about the landscape, history and food of the blues. Don't miss it!BBC iPlayer Rick Stein Tastes the Blues

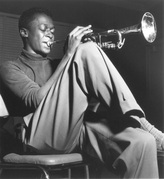

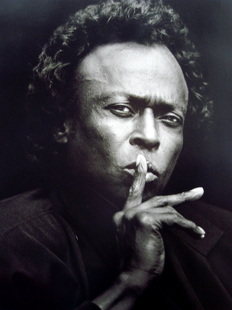

I have always been uncertain about jazz - all that random introspection with no apparent resolution. It’s such a contrast to the melody-driven tunes that are the heart of my own music. As we embark on the Jazz block of the DFM course, I wonder if I will change my mind about jazz? I’ve been listening to Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue album for the past couple of days, and one thing is sure - I like Miles Davis’ music, and I especially like Miles Davis’ trumpet playing.

Miles Davis was born on May 25, 1926 - I was born on his birthday, 27 years later.* Miles Davis belonged to my parents time, but seems to have been just too young to fight in WWII. He died young, in 1991, more in my grandparents time than his own, having suffered from sickle anaemia which interfered with his music.

Like David Honeyboy Edwards, Miles Davis was the grandson of a slave. His father was born only a handful of years after the emancipation of the slaves. Unlike Honeyboy Edwards’, however, Miles Davis’ family background was cultured and educated:

“The slave Davises played classical string music on the plantations. My father, Miles the first, ... wanted to play music, but my grandfather ... made him go to Northwestern [University] to be a dental surgeon.**

I wonder, if fundamentally, Miles Davis was a man who struggled with crossing the divides within American society of that time. There are countless and sometimes contradictory anecdotes about his being a pimp (probably true for a short time in the 1940’s to fund his heroin addiction), his heroin addiction (overcome in the 1950’s long before Kind of Blue) and his being a difficult man.

He grew up in East St. Louis (across the Mississippi from where I lived) in an area that is renowned for it’s deprivation, yet he came from an affluent family. His father was a dentist and owned a second substantial property. Even today, East St. Louis remains racially divided. East St. Louis is over 97% black; Collinsville, ten miles northeast is over 87% white.***

It is perhaps no coincidence that Miles Davis spent most of his working life in New York . When asked whether there were places he didn’t like to perform, he replied that he wouldn’t taking bookings in the south because he wouldn’t tolerate the Jim Crow attitudes.

Music was important to Miles Davis from the beginning. It was something he excelled at, although he did experience disappointments early on:

“In high school, I was the best in the music class on the trumpet. I knew it and all the rest knew it -- but all the contest first prizes went to the boys with blue eyes. It made me so mad I made up my mind to outdo anybody white on my horn. If I hadn't met that prejudice, I probably wouldn't have had as much drive in my work. I have thought about that a lot. I have thought that prejudice and curiosity have been responsible for what I have done in music.”**

Davis entered Juilliard in 1945, viewing it as his ticket to New York but found it didn’t meet his musical expectations: "Up at Juilliard," Mr. Davis said later, "I played in the symphony, two notes, 'bop-bop,' every 90 bars, so I said, 'Let me out of here,' and then I left."**** Indeed, he left to play with Charlie Parker, to become one of jazz’s most famous musician, and to create Kind of Blue, the best selling jazz album of all time.

The more I listen, the more I appreciate the understated, modal and lyrical playing. Kind of Blue wasn’t scored and rehearsed in advance - Miles Davis brought his musicians together, gave them a list of the notes he wanted them to play, and set them off. In the track So What, I particularly appreciate the simplicity of Paul Chambers double bass line, the unexpected classical ornamentation in Bill Evans piano playing, the utter purity of Miles Davis trumpet playing, and the way the music diminishes towards the end. I also particularly like Flamenco Sketches for the lovely muted trumpet solo and the contrasting dynamics between the piano and trumpet. There are many recordings and reissues available of Kind of Blue - I have enjoyed the “original jazz sound” recordings the most, as they sound more subtle, and I like the purity of the sound.

If you haven’t listened to Kind of Blue, give it a go - you won’t be sorry!* There seems to be some uncertainly as to whether his birthday was May 25 or May 26, something that seems unusual for the age, and the social milieu into which he was born.** www.erenkrantz.com/Music/MilesDavisInterview.shtml*** www.wikipedia.com**** www.racematters.org/milesdavisobituary.htm

I’ve spent the week in black, or looking at black. No, no one’s died - this week was the culmination of our first 3-week performance block. It started off on Saturday in the Queen’s Hall for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra’s innovative and entertaining film scores performance. Having ranted in a previous blog about the Usher Hall’s acoustics, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the acoustics upstairs at the Queen’s Hall. I usually sit downstairs for folk concerts at the Queen’s Hall and it’s not an easy venue - all those pillars and the hard pews. The seats upstairs are still hard, but we had a great view of the orchestra and great sound.

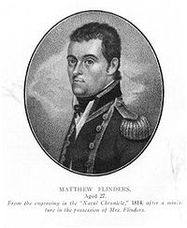

The concert included film scores by Takemitsu (lovely, I had never heard his music before and will be looking for more), Saint-Saëns (gorgeous), Shostakovic (energetic, stereotypic, comedic and compelling) and the world premiere of Gordon Kerry’s “Captain Flinders’ Musick” for flute and small orchestra. Despite my husband’s misgivings, (how well he remembers the last flute concert I dragged him to, that inscrutable Flutes of the World concert), the concert was one of the most delightful performances we have been to recently. Alison Mitchell’s flute playing was light, accurate and effervescent. Captain Flinders’ contained engaging musical figures, but might have benefitted from being longer, and perhaps in more movements, so that the melodies could have had more development.

A white cat crossed my path on my way to college on Wednesday for the Trad Band’s concert, and reappeared at my feet on Thursday on my way to the more formal classical performances. I wondered if that was a bad omen, as white lilies are a symbol of death in Japan. Having survived, I hope white’s other symbolism may be more applicable - the end of one “life” and the beginning of another.

Wednesday’s Trad Band concert was great fun, two sets with unusual arrangements that flew by in a flurry or even a scurry. I hope we get the chance to perform these again, but perhaps at a slightly slower and more comfortable speed - it’s really hard to get into a groove at warp speed!

For me, Thursday’s concert felt more relaxed. There is so much less performance pressure when the music is sitting in front of me. I’ve been surprised at how much I’ve enjoyed playing classical music in the concert band (oboe aka wooden flute) and string group (oboe aka english concertina). It’s been so companionable, sitting within a large group of other musicians, playing together. All of the octave jumps in the Handel have been great for my technique as has playing the wooden flute in the Holst Dflat section. Despite very little rehearsal time, the Shrek arrangement had a huge impact on the audience. We’re still singing “Who Let the Dogs Out” in our house, much to the consternation of the real dogs. The choir was great too, although I discovered how difficult it is to actually read the score when sandwiched in like a sardine - must learn the words before our next performance at the Usher Hall!

It’s been particularly interesting rehearsing for these performances. Both Neil Metcalfe and Laurie Crump bring a mindfulness to the musical and a clear vision for what they want to hear. I’ve learned more about phrasing from a one hour sectional with Neil than a lifetime of playing, and similarly from Laurie’s attention to the dynamic content of the Handel.

(Finally, thanks to my long-suffering husband for the title to this blog. I was going to call it “All Blacks” but thought that might be too politically incorrect. The credit is his, the errors are always all mine.)

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed