Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in Salzburg on 27 January, 1756, to musical parents. He was a phenomenally precocious child prodigy, a “wunderkind”. Talented at the piano, violin and viola, he had composed over 600 works, including operas, symphonies, and chamber music, by the time of his tragically early death at the age of thirty-five. He was friends with Haydn, a protégé of C.P.E. Bach and an inspiration to many, including Schumann and Mendelssohn.

Mozart lived during the “age of enlightenment”, when Rousseau was encouraging his fellows to cast off their chains and Thomas Paine was developing his “Rights of Man”. There was a new interest in free intellect and introspection. Mozart’s instrumental music was particularly reflective, prescient of Romantic music. While this was a fertile and creative time, patronage of the arts was in decline. The Hapsburg ruler Joseph II’s focus was firmly on socio-political priorities, and pecuniary difficulty was a common theme throughout Mozart’s life. Unlike Haydn, who benefitted from a long-term relationship with his patrons, Mozart had a tumultuous relationship with supporters and his livelihood was based in his performance skills.

The Rondo for Violin in C major, K. 373 was composed in April, 1781, shortly after Mozart took up permanent residence in Vienna. The epitome of stile gallant, the rondo is Allegretto grazioso, moderately fast and graceful, aristocratic and elegant. It was almost certainly composed for Antonio Brunetti, the celebrated Italian virtuoso violinist, although, in a letter to his father, Mozart referred to Brunetti as “a thoroughly ill-bred fellow”.

At first glance, the Rondo appears to be a simple piece with little complexity or musical depth. Unlike typical classical rondos, however, Mozart developed the form into the “sonata rondo”, with a plethora of melodic themes in just 182 bars. Floyd Grave’s analysis captures this:

“..the complementary phases of sonata- form exposition and recapitulation on the one hand, and the rondo’s customary rhythm of alternation between a tonic-key refrain and spans of intervening contrast on the other... Mozart manages to dovetail these two disparate principles, but also to confront the fact of their basic incompatibility ...he often seizes on that very incompatibility and derives from it a compositional resource of vast possibility. In essence, the friction generated by the simultaneous unfolding of sonata and rondo serves him as a foundation for strokes of surprise, suspense, and the wit of unsuspected relationship—and also, perhaps paradoxically, as a source of structural cohesion.” (Grave, “Mozart’s Problematic Rondos”)

The origin of the Rondo for Flute in D major, K. Anh. 184 is unclear, but it is almost certainly later than the violin work that it imitates. The two works are virtually identical. The flute cadenza is now written out, attributed to Jean-Pierre Rampal who was instrumental in popularizing the work. The violin rondo includes dual octave leaps where the flute version has just a single octave. The ending in the last bar is inverted - the violin finishes high on what would be the flute’s fourth octave C, while the flute finishes low on second octave D, a much more pleasing note.

It is a commonplace that Mozart disliked the flute, probably because of its unreliable tuning. He lived during a time of change and experimentation, when there was a moving away from the one-keyed baroque flute to innovations such as Quantz’ tuning slide, and Trömlitz’ new flute in which “in which each of the twelve semitones of the chromatic scale was produced by a separate tone hole not shared by any other note”. The Trömlitz flute’s pure (rather than tempered) intervals were in keeping with Mozart’s ideas on tuning. While Mozart’s flute music is gorgeous on modern concert flutes, arguably the Trömlitz flute is required if we are to play Mozart’s music as he himself would have intended.

Felix Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg in 1809, into a cultured, educated and affluent family. During a life cut short at 38, he created a huge body of work ranging from concerto’s, chamber music and incidental music, through oratorios, lieder and symphonies. He was a child prodigy who played several instruments, began composing at a young age, and is considered by some to have been even more gifted than Mozart.

The Violin Concerto in Em, Opus 64, is one of Mendelssohn’s most well-known works and one of the greatest violin concertos ever composed. Written over several years, it was first performed in 1845 and by its dates belongs to the early Romantic period. This concerto, however, is more reminiscent of Mozart than Liszt or Chopin, with its relatively small orchestra, no trombones and no separate cello part.

The first movement begins with 1 1/2 bars of tremulous strings and sustained woodwinds, heightening the anticipation of the solo violin’s innovative early entrance with the first lyrical subject. The elegance and lightness of touch often associated with Mendelssohn is there, as well as a gracious relationship between soloist and orchestra, each getting their share of the attention. The transition to the second subject has it’s own theme, this time introduced by the orchestra and then followed by the soloist. The second subject sees another reversal of roles, initiated by a woodwind “choir” with the solo violin becoming accompanist.

Mendelssohn’s written-out cadenza is another innovation, placed before the recapitulation rather than, as was more common, at the end of the movement. The cadenza demands serious violinic skill but Mendelssohn abhorred ostentatious virtuosity, viewing it as vulgar and deleterious to the music. With the placement of the cadenza in the middle, the first movement is able to flow into the second through a single note held by the bassoon. Unlike Vivaldi, for example, who encouraged audience response between movements, Mendelssohn intended the three movements of the Violin Concerto in Em to be played through without pauses between movements, enabling the audience to hear the transitions from the E minor first movement, to the the C major second movement, and the E major final movement. The whole concerto can then be seen as a musical thought. Mendelssohn’s close association with Goethe is well known, and the way in which the final movement contains antecedents from the first comprises a sort of Goethean organic development.

Mendelssohn was hugely popular during his lifetime and also renowned for his prowess as a conductor. His audience tended to be based in the German Bürgertum, the educated and cultured urban who supported the arts and had initiated a shift from purely aristocratic patronage. Mendelssohn was also the driving force behind the creation of the Conservatorium of Music at Leipzig, which became the model on which music education is still based in Germany today.

Since then, however, the social and political context of Germany has had an ongoing impact on the popularity of his music. Sadly, despite his prodigious talent, Mendelssohn’s enduring success has been inextricably meshed with the question of his Jewish background. Wagner’s allusions to a Jewish conspiracy in music became damaging rhetoric in the hands of the Nazis. There was also a feeling, more prevalent in Germany than elsewhere, that Mendelssohn was a lightweight whose familial affluence had precluded him from experiencing the angst necessary to reach greatness. Surely the brilliance of his music should rise above all these other issues but even today, for Felix Mendelssohn, social context continues to draw an uneven interest.

Henry Purcell's Dido and Aeneas has been my next research project. When I first heard the opera, I wasn't at all sure that I would enjoy it, but after all the work analysing it, I'm a real fan.

Henry Purcell was just an infant when Charles II was invited back to England, and in his mid-twenties when James II succeeded to the throne in 1685. He trained as a choir boy at the Chapel Royal, and went on to become a court composer, the organist at Westminster Abbey, and a renowned harpsichord player and teacher before his untimely death at the age of 36.

Dido and Aeneas was Purcell’s first opera and seems to have had little initial impact. After an early amateur performance at Josias Priest’s Board School for girls in 1689 (although it is unclear whether it was performed at Court previously), Dido and Aeneas remained unpublished until 1841.

The opera is in three acts. Act I opens with an Overture based on the French overture form of a slow start followed by a fugal second part. Lovely arias including “Shake the cloud from off your brow”, and “Ah Belinda, I am press’d with torment” are interspersed with choruses and “recitatives” (speech-like solo singing). The first act concludes with an uplifting chorus “To the hills and the vales” followed by an enchanting instrumental dance, “The triumphing dance”.

Behind Purcell’s beautiful music and Nahum Tate’s libretto setting of the Aeneid, lies a world of political uncertainty, constitutional upheaval and social critique. The opera is full of characters who give or receive bad advice, all of it ultimately shown to be ill-considered and misguided.

There is controversy around the dating of the work. Those who date it before the Glorious Revolution of 1688, suggest that Dido and Aeneas is a political allegory, critical of the breakdown of constitutional principles and the subsequent undermining of the divine right of kings. If dated at 1689, Dido and Aeneas can be viewed as a criticism of the new monarchs, Dutch William of Orange, and his wife Mary, the daughter of the deposed James II. It may even be a warning to William to treat Mary well. Either way, Dido’s death is unusual and foreboding in an opera of the period, and coincided with Purcell’s declining popularity in the new Court.

Musically, Dido and Aeneas demonstrates Purcell’s genius. He was skilled at “word painting”, using music to embody meaning, as for example the dissonance when Dido sings “Peace and I are strangers...”. Purcell did not create word painting, it was frequently used in Elizabethan and Baroque music, but he was a master at it. Similarly, he had a gift for English prosody, accurately recreating the rhythms of the English language in his music.

Purcell also showed extraordinary talent in the way he employed musical keys to underlie the drama. Most of the opera is in C minor, which represents pain and suffering. Happier scenes, such as the lovely “Fear no danger” duet and chorus are set in C major, the “royal” key. F major is Purcell’s love key and G minor is his death key, used as foreshadowing in “Ah Belinda” and then towards the end of Act III in “Dido’s Lament”.

Over two hundred years after Purcell composed Dido and Aeneas, a group of music students, including the young Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst, were instrumental in reviving the opera for the 1895 bicentennial of Purcell’s death. Today, it is still frequently performed and recorded. Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas may have been ‘just’ a small opera, but it continues to illuminate a watershed in English history and is cherished as early English music.

I'm studying classical music research and analysis techniques this year - very exciting stuff. For the first assignment, I focussed on the 3rd, Allegro, movement of Haydn's Trumpet Concerto in E-flat Major, Hob. VIIe: 1. I have always liked Haydn, and it's been really interesting to look at the music from a more rigorous perspective, and to learn about the development of the trumpet.

Franz Joseph Haydn was born in Austria in 1732, the year that Benjamin Franklin began to publish his Almanac a continent away. Haydn spent much of his adult life as musical director to the Hungarian Esterhazy Princes, living through the French Revolution, the American Revolutionary War and the rise of the Industrial Revolution. Like Handel, he spent time in London and was much loved by the British people. He was Mozart’s friend, Hummel’s mentor and a prolific composer. Haydn died in 1809, leaving behind nearly 500 works, including some 108 symphonies and 17 concertos. The Trumpet Concerto in E-flat Major (Concerto per il clarino, E flat) was the last concerto he wrote.

In his sixties, with an established international reputation and an Honorary Doctorate from Oxford, Haydn composed the Trumpet Concerto in E-flat Major specifically for the new “organised” (or keyed) trumpet. Anton Weidinger, perhaps the most virtuoso trumpeter of his day, had invented this trumpet in order to broaden the technical and artistic range of the E flat trumpet. Previously, the Baroque trumpet’s chromatic scope had been limited to the upper two octaves, known as “clarino” (clarion) playing, with much playing done in the more normal court or military “principale” range. By the end of the 18th century, clarino technique had all but died out, with the trumpet relegated to military fanfare use, or solely as a member of the orchestra. It was hoped that Weidinger’s keyed trumpet would enable a fuller chromatic range as well cantabile expression.

The Trumpet Concerto in E flat, composed in 1796 but not performed until 1800, ushered in a new repertoire for the trumpet. It is widely suggested that the reason for the four year delay before the first performance was due to Weidinger’s need for ample time to learn the new instrument and be able to play the solo part. While this concerto is one of Haydn’s most well-known works today, it made little impact at it’s debut and was then lost until 1929. Similarly, Weindinger’s innovation failed to endure although it did lead the way to the valved trumpets still played today.

Movement III, Allegro opens with the orchestra playing a compelling and memorable melody that is recycled throughout the work. This melody is then taken up by the solo trumpeter, with the orchestra acting as accompaniment. For today’s audiences, used to hearing modern trumpets, the simplicity of the main theme masks the extraordinary technical advances made possible by Weidinger’s trumpet. Haydn alternates between military rhythms recalling the trumpet’s previous role, and virtuoso displays including octave leaps, innovative changes of key, and chromatic scale and trill passages comprised of notes that could not previously have been played. At the end, the soloist returns to the trumpet’s lower principal range, almost as if to suggest that all the pyrotechnics were just an illusion, and it’s just an ordinary trumpet, after all.

Last Thursday was my recital for the Degree Foundation Music course, never been from my mind since I started the course. Despite only taking up silver flute in November, I really wanted to play all three of my instruments in the performance, and was lucky to find a fantastic Boehm flute teacher in February to help me with technique. Having had such fun playing baroque music in the string group, the casual suggestion from my college tutor that I could play a Handel sonata (“grown up music”!) really captured my imagination. From March, not a day went by when I wasn’t playing Handel’s Sonata in F major - as well as hearing it in my mind in the middle of the night, on the bus... everywhere.

The Sonata in F major was one of eleven sonatas written by Handel in the mid-1720’s, often referred to as Opus 1 Number 11, or HWV369. The collection was first published by Walsh in about 1730, although the published manuscripts did not always designate the original instrument that Handel had composed for.

Sonata XI was published “fur Blockflote und Basso continuo”. Blockflote, also known as flauta, indicated a recorder. The Boehm flute was not invented until the latter half of the nineteenth century, and while there were baroque flutes during Handel’s time, these were referred to as querflote or traversos. Of course, playing Handel on a Boehm flute is no more authentic than playing Holst on a Rudall and Rose flute... but it sure is fun.

Handel’s recorder sonatas, according to David Bryson,“were the product of his association with first the Earl of Burlington, whose interest in the arts was genuine, and later with the Duke of Chandos who was a bit of a poseur and opportunist.” All of the sonatas have four movements, based on the “sonata da chiesa” (church sonata) format. The sonatas are not church music, however, but were intended to be "tafelmusik" (played for feasts or banquets) or informal music, played by a family or group of friends. Interestingly, Handel reused much of Sonata XI in the later Organ Concerto V.

The Sonata in F has been frequently recorded by both recorder and flute players. I learned this work from Bärenreiter’s urtext edition, but also looked at other versions on imslp.com. It is astonishing how different the versions are, particularly in phrasing, articulation and metronome markings. I also listened to a variety of recordings, both recorder and flute. Some recordings are completely bare of ornamentation, while others were almost diametrically opposed across the movements in tempo. I really enjoyed Marion Verbruggen’s recording (probably the baroque stylistically correct) and Laurel Zucker’s flowing flute rendition. It is believed that Handel intended for ornamentation to be added to his sonatas, both in the slower movements that are played only once, and certainly in the repeated sections of the allegro movements. In the end, I listened widely and distilled my phrasing and ornamentation to best express the piece for myself.

I also played a set my Rudall and Rose flute, of a gaelic air and two jigs, plus an unknown slow reel on the concertina, that may be a Norwegian wedding march. Laurie Crump accompanied the wooden flute set, and the Handel Sonata, on harpsichord which was lovely, and provided a great balance for the flutes. He also put together a gorgeous piano accompaniment for the concertina set. The programme went well, and was well-received, as were my programme notes:

| DFM Recital Programme Notes | | File Size: | 2398 kb | | File Type: | pdf |

Download File

On the whole, I was pleased with the way I played, and despite my nerves, managed to breathe my way through the whole programme. Nerves do affect breathing and flute tone, however, and I wish I could have relaxed more to let the flutes sing out as they do when I’m practicing at home. Conversely, playing the concertina, I was so focussed that it seemed as if I was in a bubble with all the time in the world , and it was possibly my best ever concertina playing. The concertina can be an unpredictable instrument to perform on (or perhaps I just haven’t played it for long enough). Forty eight buttons to find with six fingers and no line of sight - in my last warmup before the performance, I was shocked by how many wrong notes it’s possible to play! The pianist Stephen Hough’s recent tweet comes to mind: "Sometimes adrenaline powers the hands; sometimes it sours the stomach." After weeks of worry, some sleepless nights, and hours of practice, the adrenaline helped my focus on the concertina and my fingers on the flutes, but I don’t think it helps relax the flutes’ tone - I need to work on that.

I recorded the entire programme on my phone - have a listen to the Handel Sonata below:

It’s been a weekend of astonishing music from across the North Sea and Iceland. Northern Streams, now in its ninth year, never fails to inspire me with the diverse and excellent music showcased. What did surprise me was the different paths that the Swedish and Norwegians musicians have taken to arrive in their music.

Melodeon player Rannveig Djønne’s performance with singer and hardanger player, Annlaug Borsheim, in Saturday evening’s concert was an example of sheer beauty in simplicity. At Saturday afternoon’s last workshop, Rannveig Djønne was disarmingly unassuming. She commented on her lack of musical training, but added that she did know the names of the harmony buttons on her three differently tuned melodeons! The first Norwegian to play her country’s traditional music on the melodeon, she recounted how she attended the traditional music college some 29 years ago. And then she played Bambas, a lullaby written for her oldest niece (and told a story about writing a more fiery tune for her younger niece, a “little viking”). We were all blown away by the sheer beauty, of the tune, of her playing, of the arrangement. It was the most beautiful melodeon playing I have ever heard, her use of the fully extended bellows was amazing. Click on the picture to have a listen - her music will stay with me forever.

Similarly, singer and hardanger player, Lajla Buer Storli, told us in her Saturday morning workshop, that she doesn’t read music, and has minimal music theory. To learn some of the oldest Norwegian tunes on manuscript, her husband plays them from the sheet music, and she then learns them by ear from him. In her workshop, she taught us an old Halling and a waltz that she believed may have come from the UK, by way of the tourist boats that visited Norway, resulting in cross-cultural music influences. Ditte Mortensen, fiddle player with Danish Bornholm-based band, Habbadam, has previously expressed a similar belief in the way that Bornholm’s eighteenth century music seems to have a link with Scottish baroque music.

Fiddle player Emma Reid and saxophonist Daniel (formerly Carlsson) Reid have come to their music from more “conventional” routes. I first met Daniel at Northern Streams three years ago, when he performed as part of the band, One Fine Day, and co-taught a flute workshop with the scottish wooden flute player, Calum Stewart. This year he performed with his wife Emma who was born in Northumberland to a Swedish mother and moved to Sweden 12 years ago. The combination of fiddle and saxophone is unusual but works extremely well. In the afternoon workshop, the Emma taught us a lovely slang polska, and then Daniel demonstrated modal drones and rhythmic riffs as effective harmonies. Daniel has a broad background in classical music as well as jazz and folk, and teaches at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm while Emma graduated from Newcastle University and then the Royal College of Music in Stockholm. Their music is firmly rooted in the Swedish tradition, imbued with rhythm but at the same time articulate and with well-honed technique.

For me, the stars of Friday night’s concert were Karin Ericsson Back and Maria Misgeld. Singing acapella. Two of three members of the band Irmelin, their harmonies and canons were entrancing. They committed wholly to the music and were a joy hear.

All of these Nordic musicians are so generous with their time and their art. They invited us whole-heartedly into their music, sharing with us as they themselves have had other traditions share with them. Shetland’s music is acknowledged as a continuing influence, as are the other nordic countries. The only disappointing thing about Northern Streams 2012 was the paucity of the audience in both the concerts and the workshops. Northern Streams is such a great opportunity to expand musical horizons. Why are so few of us interested in engaging with our northern neighbours...

Recently, I’ve been working on Telemann’s Concerto in E minor for Two Flutes with Basso Continuo TWV 53: e2, Burn’s Highland Mary, a set of contemporary strathspeys ending with a jig, a set of polkas and Handel’s Flute Sonata in F for my recital (more of that in another blog).

We’ve just come to the end of the third performance block, and what a joy it’s been making music together, although music is such a conundrum. After rehearsing the Telemann, in which I played Concertante (solo) flute 2, I come away all serene and think to myself that I can play the flute. After a wind band rehearsal of Copland’s Salon Mexico, where the first flute part is at the absolute top of the range and I can hardly play it (too much shrieking!), I come away wondering whether I will ever be able to play the flute. It’s a balance - playing baroque music is intangibly joyful while mastering something like the Copland will be an achievement. I know that if all the music I played was easy, it wouldn’t be an enduring pleasure and it wouldn’t keep my attention for a lifetime.

It’s not surprising that Telemann was so prolific. Born in 1681, he lived until he was 86, dying in 1767. The Oxford Music dictionary observes that “He remained at the forefront of musical innovation throughout his career, and was an important link between the late Baroque and early Classical styles. He also contributed significantly to Germany’s concert life and the fields of music publishing, music education and theory.” He composed over 1000 works, of which at least 125 were concertos. Many of these were “tafelmusik”, smaller scale pieces designed for domestic music-making. I would have like to know more about when and why Telemann composed this work. I have been unable to find information specific to the concerto we played, but it appears to have been composed around 1720 - 30. Have a listen - (I've removed the clapping between movements, and normalised the recording in audacity).

Concerto Grosso in E minor for Two Flutes and Bassoon - Stevenson College String Group:

In a completely different genre, some utterly simple tunes like Highland Mary are so beautiful in themselves that they transcend everything else. Our arrangement, which weaves instrumental interludes around the solo voice, never failed to create a shiver down my spine - so lovely.

Highland Mary - Stevenson College Trad Band:

While I’m looking forward to enjoying the Easter holidays, I have already started having nightmares about my recital and there’s so much work to be done for theory! Onward... and onward.

The BBC has outdone itself recently with it’s classical musicology programming. Simon Russell Beale’s “Symphony” series was shown at the end of 2011, and Charles Hazlewood’s “Birth of British Music” , originally produced in 2009,is being shown again on BBC 4. This series looks at four 17C - 19C composers, Purcell, Handel, Haydn and Mendelssohn. Perhaps the irony of the German view of Britain as the “the land without music”* is not lost in the fact that in “The Birth of British”, only Purcell was actually British.

I only managed to catch the “Revolution and Rebirth” episode of Symphony, in which Beale looked at the symphonic works of Shostakovich, Ives and Copland. Wonderful music especially, for me, because all three composers incorporate their sense of culture and country into their music. I first heard Charles Ives’ Fourth of July (from the Holidays Symphony) when I was in secondary school, and I remember laughing out loud at the accuracy of the portrayal of one of America’s most “sacred” holidays. I listened to it again today, and while it starts darker than I remember, the later section still makes me laugh.

We were very fortunate, at Stevenson College in the early part of February, to have the opportunity to hear Tim Paxton (cello) and Simon Coverdale (piano) perform a Shostakovich cello sonata. In his introduction, Paxton referred to Shostakovich’s ability to be "everything for anyone", a technique that enabled him to surviving the totalitarian regime under which he spent his entire life. Much of his work was double-edged and ironic, embodying the requirement to be a good proletarian composer, his own struggle for identity and his alienation from the regime. The cello sonata was a very dark work, such despair, and though the mood lightened somewhat by the end, the music held no assurance that everything would be all right.

While the concept of the ”land without music” looks at the dearth of formal, classical composers in Britain, it also reveals a snobbish ignorance of the plethora of vernacular music throughout the British Isles.

Ordinary people have enjoyed vernacular music all over the world since time in memoriam. Scotland, Ireland, England and the Nordic countries, in particular, have rich folk musical traditions which have been woven into the music of formal composers such as Handel, Vaughan Williams, Sibelius and Grieg. Others, such as Mahler and Shostakovich, have written big, gorgeous works incorporating folk melodies at the heart of the music. Even in young countries like Canada and the United States, the melodies of the developing communities have been captured by such as Charles Ives and Aaron Copeland.

In all things, labels can be used either to gather together, or to separate. It’s not uncommon today to hear classical musicians say, “I’m not a folkie”, with the implication that folk music is something too informal or too primitive to have value. Folk music is about melody - usually simple but extraordinarily beautiful melodies. Those folk melodies have found their way into bigger, more complex music - and where would that music be without them?

* "Das Land ohne Musik" - “The earliest source yet given for this rather persistent German generalisation – for the French, I believe, have never concerned themselves much with English musicality at all – is Carl Engel's book of 1866, which Oskar Adolf Hermann Schmitz in his Das Land ohne Musik : Englische Gesellschaftsprobleme quotes as a reference. In fact the prejudice held by the Germans in this respect must be adjudged of rather earlier origin than even that.” http://www.musicweb-international.com/dasland.htm

I was watching the BBC’s Imagine programme, Simon and Garfunkel - The Harmony Game recently. Well worth watching for the discussion of how the album, Bridge Over Troubled Water, was recorded and the musical influences that went into it. The thing that stood out for me the most, however, was the furore that was caused by their “humanistic” ethos during the making of Songs of America, a CBS TV special about the duo, filmed in 1969 and originally funded by one of the major telephone companies. Apparently millions of Americans turned to a different channel because of their unhappiness with political content of the show. Songs of America was criticized for being biased towards the Democrats, because it referred to the assassinations of John and Bobby Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, while Coretta King’s comments on child poverty were dubbed out. Yet, the reaction to the programme makes sense if you look at the social identity of the two. SImon and Garfunkel were two middle-class jewish boys from New York, key players in the American folk music scene of 60’s - 70’s. They were listened to by scores of other white, middle class, educated liberal young people.

After the Revolutionary and Civil wars, Americans are used to referring to their society as “classless”, and yet social background has always played a huge role in the music that people listen to. The Blues grew out of destitution of ex-slaves in the south. Jazz had it’s roots among African Americans in more urban areas, influenced by the blues.

Folk music, as played by Joan Baez, Judy Collins and James Taylor from the late 1960’s, was embraced by the anti-Vietnam war movement, and embraced the end of segregation by supporting the civil rights movement. You wouldn’t have found many white collar workers or Ku Klux Klan members listening to folk, which they viewed as “pinko” (leaning to the left) music.

Similary, country music grew out of the folk instruments that had been brought to areas like the Appalachian mountains by poor white European immigrants, and spread through southern and south western white communities. You didn’t find many Country Western musicians in Boston or Woodstock in the 70’s.

Numerous research projects have looked at the sociology of music: “..the relationship of youth to music was found to differ significantly along a number of dimensions, particularly those of social class, gender, and ethnicity.”* Numerous books have been written on the subject: “The music industry daily invents and redesigns labels to market musical products as new and / or authentic.”**

So how do you know what genre a particular musician belongs to?

You can look at the classifications of music shops such as itunes, amazon or play.com but that may tell you as much about the business goals of those websites as it does about the musicians.

You can look at the music’s harmonic structures, but there’s a big overlap between folk, country and rock. You can look at the social strata of the people who listen. You can look at the genre of the radio stations that play the music.

You can ask the musicians themselves for a more valid definition. Canadian Neil Young’s early music leaned towards folk, he had a period of anti-establishment protesting embodied in the cd Living with War Today, but some of his later work he himself refers to as country rock. Or you could ask the listeners what genre they would given a particular musician.

Over time, people’s perceptions of genre change and the genre themselves are influenced by other musical influences. Jazz turns white and country turns popular.

Does it really matter, anyway? Well, I can think of more than a few Scottish traditional musicians who would object to their music being referred to as Morris tunes - even though there’s a large overlap between Scottish, English and Irish music. I just think you have to be aware of the power of cultural insensitivity... and try to avoid it, if you can.

*/www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/DATABASES/MIE/Part2_chapter03.shtml

**Fabian Holt, Genre in Popular Music. Also Edwards, Leigh H., Johnny Cash and the Paradox of American Identity, and Eyerman, Ron, Music and Social Movements: Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century.

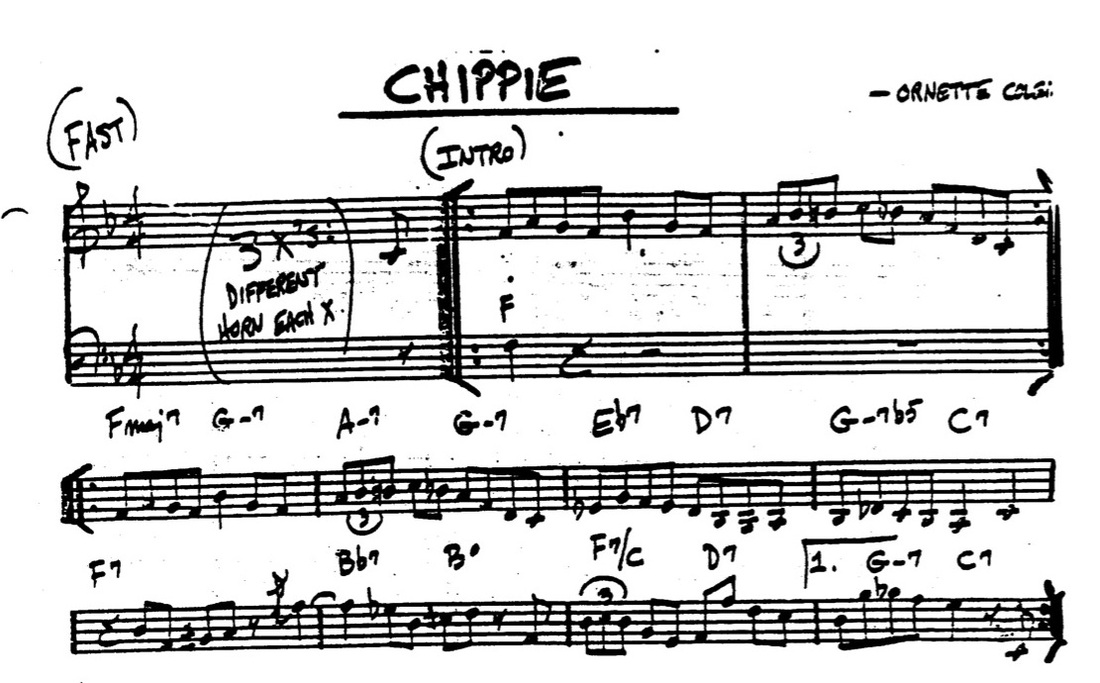

While I may not be a jazz aficionado, I am interested in learning how to analyze a jazz lead sheet, comprised of the “head” (main melody) and “chorus” (chord sequence, once through).

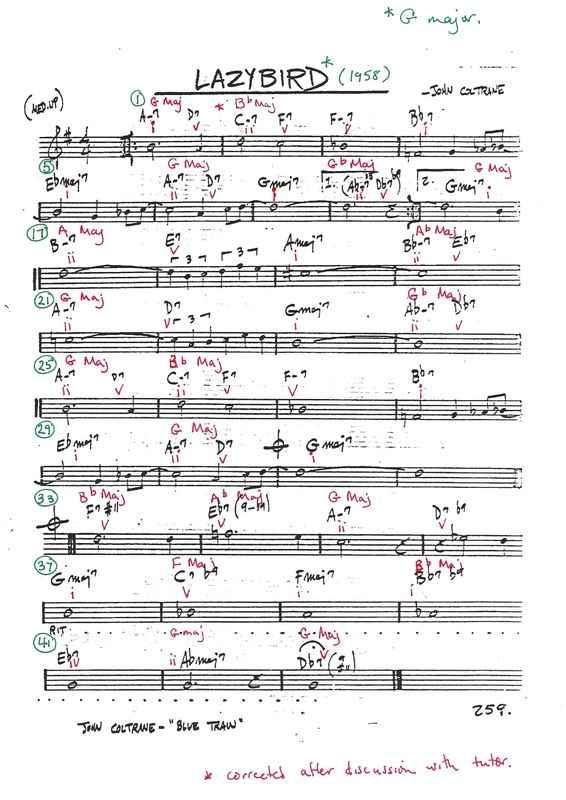

I’m fascinated by the way jazz musicians create chord sequences first, and then fit melodies and improvisation to the harmony. As a traditional musician, I work in the opposite way, composing a melody first, and then just playing it with other musicians, hoping the guitar player will be able to figure something out! Surprisingly, some of the jazz melodies are really lovely - and would sound almost like traditional music if played slowly, with a different harmonic base. See the opening melody in Ornette Coleman’s tune “Chippie” below: Analyzing a Jazz Song - John Coltrane's Lazy Bird John Coltrane was born in Georgia in 1926, the same year as Miles Davis, and like Davis and Honeyboy Edwards, he was the grandson of slaves. However, his maternal grandfather, Reverend William Wilson Blair* had become a religious and political leader in his community, and Coltrane was raised in a religious home. He attended a High School for African American students opened by his grandfather, and then went on to music school. He was a multi-instrumentalist, playing saxophones, horns and even the flute. In 1945 he enlisted in the US Navy, and was stationed in Hawaii where he played in the Navy jazz band. He was part of Miles Davis’ band for Kind of Blue, and is quoted on johncoltrane.com as saying”Miles music gave me plenty of freedom”. 1958, John Coltrane released his Blue Train album on the Blue Note label. It is considered to have been his favourite album. Blue Train was post bebop but pre-free jazz - I found numerous references to the style as “hard bop”. Lazy Bird, the jazz song I’m going to try and analyze below, was the last track on Side 2 of the LP, was written by John Coltrane himself, and lasted 7 minutes.

Lazy Bird is in 4/4 in the key of Gmajor. The A-part is 16 bars long in total, made up of 7 bars that repeat, with different 1-bar tags for the first and second endings.

The B-part is 16 bars long, made up of a 4-bar melodic figure that is repeated a whole tone lower (8 bars), a 3-bar melodic phrase, and then a small ascending [crotchet / quaver quaver / minim] figure used three times and including a [tied quaver minim] that crosses over a bar line.

The harmonic structure is:

A-part:

Bar 1: Chord sequence is ii v of G major

*Bar 2 - 5: Transition to Bflat major with backdoor sequence ii v i

Bar 6 - 7: The key is back to Gmajor ii v i

Bar 8 - 1st ending is ii v of Gflat major with complex chords Aflat minor13 and Dflat7flat9 / 2nd ending is i of G

B-part:

Bars 17 - 19: The key has changed to Amajor ii v i

Bars 20: Change of colour using the ii v of Aflat major

Bars 21 - 23: Back to the root of Gmajor in ii v i

Bar 24: Change of colour as in bar 20 using the ii v of G flat major

Bars 25 - 32: Identical harmonic structure to Bars 1 - 8 of A-part, a very lazy bird indeed.

Coda:

I’m assuming the cross-hatched circle symbol is a a coda played before the end. If the final chord is the Dflat 7 (9 # 11), then the song finishes on a v chord, but if the final G chord is played after the end of the previous chord, then the song ends on a v i cadence.

The chords in the coda are more complex, including a #11, 9 and flat 9’s, and a 9 #11 . I don’t have the experience to really understand why these chords have been included, but I guess they add extra colour to the coda improvisation.

Bars 33 - 34: Descending key sequence: v of Bflat / v of Aflat

Bars 35 - 37: Descends back to G major ii v i sequence

Bars 38 - 42: Continues to descend: v i of Fmajor / v of Eflat major / v of Aflat major. However, Eflat7 chord in bar 41 could be a substitute for an Eflat major7 chord which would make a i iv sequence in Eflat

Bar 43: finishes with v of Gmajor

*corrected after discussions with teacher This is the first piece of music I’ve ever analyzed in this way, and no doubt there are better methods or language in which to do this. Lazy Bird opens with a simple melody, but It’s been interesting to find the patterns, both melodic and harmonic, which I've been unaware of just listening to the music. I’ve been surprised by the number of chords in flat keys in a song that’s in a sharp key. Analyzing the song gives me a glimmer of understanding, where previously bebop and free jazz have been pretty much impenetrable to me. It would be interesting to analyze the improvised solos in the same way, but that would be even more time-consuming and a topic for another blog (in another lifetime?!?).

*John Coltrane and Black America’s Quest for Freedom - Spirituality and the Music, edited by Leonard L. Brown, Oxford University Press, 2010. p. 146

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed