In the not so distant past of my youth, planning was something you did on paper, and research was something you did on index cards. There was a whole world of stationery to relish - yellow pads in different sizes with different sorts of lines or grids; index cards in different sizes with boxes to hold them and index dividers.

How the world has changed! Planning tools are now digital - and the internet provides more research possibilities than I would ever have thought possible. For me, however, the root of planning is still the list, in paper or digital form.

As I sit in my college classes, I’m surprised to find that I am one of the few who always takes notes. It’s a habit - I write everything down. I never know when I’m going to want to retrieve a piece of information that I’ve heard, and the act of writing something down helps me remember it as well. If I haven’t taken notes, how will I be able to find that information? I carry a little pad in my handbag, and another in my instrument backpack. I write down ideas that I have for working on later. I write down cool things that people say, titles of books that I see in bookshops, tune titles in sessions. I go back and look at my class notes, and make lists of all the things I need to learn - and then I have the self-indulgent pleasure of ticking off the lists as I work through them.

Planning is more than lists, however. Since there is never enough time to practice everything during my instrument practice, I prioritize my practice:

- Warmup - Breathing exercises first with the metronome on counting how long I can go on one breath, followed by long notes on the flute, again with the metronome, or scales on the concertina, and warmup tunes

- Time dependent practice - the things which need to be played publicly soonest, whether for performance, band practice or private lesson

- Technique practice - rolls, ornaments, dynamics, phrasing. Sometimes I work on these in isolation, but more often I play tunes that focus on aspects of technique

- New Tunes - always a pleasure but not an essential

I prioritize my classwork in a similar way, working on things that are date sensitive first, and using lists to remember to work steadily on more long-term work like this blog. Both my practice and classwork are heavily computer-reliant. Some of the tools I use are:

Audacity - free shareware for mac or pc for recording yourself playing, back mp3’s or a range of other recording formats. I use audacity to record my long notes on the flute, so that I can gauge my progress and hear the level of support in the notes. I also use it to regularly record myself practicing, and occasionally keep dated versions of tunes to compare my progress. Audacity has options for slowing down recordings to help learn tunes, selecting sections of tunes, and normalizing recordings.

Evernote - an astoundingly good app for collecting information in notebooks, which then sync wireless across the mac range and are also available on the internet. The Evernote Clipper clips and stores web pages complete with website reference. The notebooks can hold media clips, images and text. Similar in some ways to microsoft's OneNote application.

Cleartune - the best, most inexpensive, tuner I’ve ever seen, available for the iPhone / iPad and other smart hardware

Ludwig and Steinway Metronomes - free for iPhone / iPad

OpenOffice.Org - database software. For more than a decade, I’ve kept a database of the tunes I’ve learned, who I’ve learned them from, their origin, key, and first couple of bars in abc format. I can retrieve tunes I haven’t played in this way. I once heard a story about Paddy Fahy, the very famous Irish composer and fiddler, born in 1926. He farmed for a living, and associated his tunes in his head with areas of the farm such as the fields where he had composed a particular tune. The tunes didn’t have names, were unpublished and referred to as in Paddy Fahy’s No. 2 jig. The story goes that when, later in his life, he moved to a new house in a new area, he could no longer remember lots of his tunes and because they weren’t ridden down, they may be lost forever. Had he kept a database like mine, that wouldn’t have been a problem!

I still have one of my brown index box cards, but I only use it these days to store “old treasures”. Computers provide much better indexing and planning tools, and have made it so much easier to collect and keep track of information. One thing will never change for me though - the need to remember Pareto’s 80 / 20 principle, to focus 80% of my time and effort on the 20% of work that has the highest impact.

Do you use any other great planning apps or music tools? Feel free to share them in the comments.

Artist unknown.

I am finding jazz a challenge, although there have been some surprises. I thought I would prefer to move forward in the jazz timeline to get away from all the racism African American musicians experienced at least before the 1970‘s. I find, however, that listening to a lot of contemporary jazz makes me feel uneasy or even downright uncomfortable. I listened to a Christian Scott youtube clip, and while the trumpet and piano playing was fine, (although perhaps not as lovely a tone or as expressive as Miles Davis), I found the drummer’s playing completely inscrutable - no pulse, no evident rhythm, just what seemed like a cacophonous background. I just don’t get it and I just don’t enjoy it.

Jazz doesn’t seem to have a specific definition, but ranges over lots of different styles, including: Bebop, Dixieland, Cool, Jazz Funk, Modal, Acid and Cool. Oxford Music Online defines jazz as resulting “from three developments: the addition of blues rhythms and pitch inflections to rags and other popular song and dance forms; the undergirding of rags and other two-beat forms with a 4/4 ground beat; and the uneven playing of eighth-notes.” The Kennedy Center (NYC) website defines jazz as a feeling of triplets behind a basic beat giving a swingy style to the music, improvisation, reliance on sycopation and an AABA song form. ( Oxford Music Online and www.kennedy-center.org)

It’s hard to define what I look for in music, and to specify what I like. Unfortunately, it’s been easy to find jazz that I don’t enjoy. The list of who I reallydon’t enjoy includes Steven Coleman, Lydia Lynch, Keith Parker, Charles Mingus, Johnny Hammond Smith and Stefan Grupelli. The list of who I just feel unengaged by includes Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Thelonius Monk. (spotify.app) I guess that what I look for in music is a structure, a melodic framework with repetitions that are mostly predictable, sometimes unexpected, but develop in an understandable or even comfortable way. Most traditional music has this sort of pattern. For example, 2/4 pipe marches are mainly in four parts, AABBCCDD or often AABBCCDA, and are usually played twice. Polskas and waltzes are usually in AABB or AABA form where the initial melody of the A part becomes the closing phrase of the B part providing a simple musical resolution. I can whistle along to this sort of music and be part of it in a way that I find unaccessible in the jazz of the musicians mentioned above.

I have been stunned to discover, however, that Louis Armstrong’s songs performed with Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby or Duke Ellington are classed as jazz. I have been equally stunned to discover that I really enjoy hearing these songs. They take me back a long way. They have beautiful melodies, optimistic lyrics and gentle improvisations providing a varied texture to the music. It’s interesting to hear younger musicians like Michael Buble and Jamie Cullum harking back to this period and both reproducing these songs, and writing new music in this style. On the one hand, I find myself feeling entirely politically incorrect in enjoying listening to a man who was the grandson of a slave sing, in his rich voice, What a Wonderful World. On the other hand, I find the voice, words and music moving, beautiful and so optimistic, a nice change to the doom and gloom that surrounds us. Louis Armstrong was a huge success in America, although he was considered by some of his fellow African Americans to be an Uncle Tom. He was welcomed in hotels and venues that were closed to most other black people. He was revered by the same white America that ordered his fellow blacks to sit at the back of the bus because of their colour.

Much of the world’s music has been born out of suffering, politicization or denial: Mahler’s denial of his jewish background, Shostakovich's’ role as the propaganda voice of the Soviet Union and subsequent denouncement, Jerusalem as an expression of the English colonial regime, just to cite a very few examples. I have to believe that music transcends the circumstances under which it was created, or else deny myself huge swathes of music that I enjoy.

Despite the incongruity of his life, Louis Armstrong’s success may have been a tour de force against segregation and racism, working within the system rather than outside as some, like Malcolm X, prescribed. However, much as I enjoy listening to Frank Sinatra sing a jazz version of Chestnuts Roasting in an Open Fire, it does feel that this sort of jazz is typical of the way in which the US dilutes other people’s cultures, a sort of Tex-Mex version of jazz. I’ll continue to listen to these old gems but I am mindful that the white American popularization of an essentially black art form is a form of the American cultural imperialism that threatens world cultures today. At the other end of the timeline, I have discovered Nu Jazz and Norwegian Jazz, and am so enjoying listening to the beautiful melodies of musicians like Bugge Wesseltoft and the Esbjorn Svensson Trio ((est) www.myspace.com/esbjornsvenssontrio).

Have a listen to est’s Believe Beleft Below (Seven Days of Falling) or Bugge Wesseltoft’s Mitt Hjerte Alltid Vanker (It’s Snowing on My Piano cd, 1997). In Bugge’s lattest cd, Kammermusik (Wesseltoft Schwarz Duo cd, 2011, www.buggeandhenrik.com) he combines jazz elements (some generated by Schwarz on his laptop) with melodic piano lines that would have been at home in a completely different age. Nu Jazz’s pensive and lyrical playing in no way resembles the music of Miles Davis or Dizzy Gillespie, and yet, it all appears to be jazz.

That’s hard to understand.

So what are your views on jazz and the politicisation of music? Feel free to comment below!STOP PRESS - I've just stumbled across an amazing Rick Stein programme on the blues! Very interesting, about the landscape, history and food of the blues. Don't miss it!BBC iPlayer Rick Stein Tastes the Blues

I have always been uncertain about jazz - all that random introspection with no apparent resolution. It’s such a contrast to the melody-driven tunes that are the heart of my own music. As we embark on the Jazz block of the DFM course, I wonder if I will change my mind about jazz? I’ve been listening to Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue album for the past couple of days, and one thing is sure - I like Miles Davis’ music, and I especially like Miles Davis’ trumpet playing.

Miles Davis was born on May 25, 1926 - I was born on his birthday, 27 years later.* Miles Davis belonged to my parents time, but seems to have been just too young to fight in WWII. He died young, in 1991, more in my grandparents time than his own, having suffered from sickle anaemia which interfered with his music.

Like David Honeyboy Edwards, Miles Davis was the grandson of a slave. His father was born only a handful of years after the emancipation of the slaves. Unlike Honeyboy Edwards’, however, Miles Davis’ family background was cultured and educated:

“The slave Davises played classical string music on the plantations. My father, Miles the first, ... wanted to play music, but my grandfather ... made him go to Northwestern [University] to be a dental surgeon.**

I wonder, if fundamentally, Miles Davis was a man who struggled with crossing the divides within American society of that time. There are countless and sometimes contradictory anecdotes about his being a pimp (probably true for a short time in the 1940’s to fund his heroin addiction), his heroin addiction (overcome in the 1950’s long before Kind of Blue) and his being a difficult man.

He grew up in East St. Louis (across the Mississippi from where I lived) in an area that is renowned for it’s deprivation, yet he came from an affluent family. His father was a dentist and owned a second substantial property. Even today, East St. Louis remains racially divided. East St. Louis is over 97% black; Collinsville, ten miles northeast is over 87% white.***

It is perhaps no coincidence that Miles Davis spent most of his working life in New York . When asked whether there were places he didn’t like to perform, he replied that he wouldn’t taking bookings in the south because he wouldn’t tolerate the Jim Crow attitudes.

Music was important to Miles Davis from the beginning. It was something he excelled at, although he did experience disappointments early on:

“In high school, I was the best in the music class on the trumpet. I knew it and all the rest knew it -- but all the contest first prizes went to the boys with blue eyes. It made me so mad I made up my mind to outdo anybody white on my horn. If I hadn't met that prejudice, I probably wouldn't have had as much drive in my work. I have thought about that a lot. I have thought that prejudice and curiosity have been responsible for what I have done in music.”**

Davis entered Juilliard in 1945, viewing it as his ticket to New York but found it didn’t meet his musical expectations: "Up at Juilliard," Mr. Davis said later, "I played in the symphony, two notes, 'bop-bop,' every 90 bars, so I said, 'Let me out of here,' and then I left."**** Indeed, he left to play with Charlie Parker, to become one of jazz’s most famous musician, and to create Kind of Blue, the best selling jazz album of all time.

The more I listen, the more I appreciate the understated, modal and lyrical playing. Kind of Blue wasn’t scored and rehearsed in advance - Miles Davis brought his musicians together, gave them a list of the notes he wanted them to play, and set them off. In the track So What, I particularly appreciate the simplicity of Paul Chambers double bass line, the unexpected classical ornamentation in Bill Evans piano playing, the utter purity of Miles Davis trumpet playing, and the way the music diminishes towards the end. I also particularly like Flamenco Sketches for the lovely muted trumpet solo and the contrasting dynamics between the piano and trumpet. There are many recordings and reissues available of Kind of Blue - I have enjoyed the “original jazz sound” recordings the most, as they sound more subtle, and I like the purity of the sound.

If you haven’t listened to Kind of Blue, give it a go - you won’t be sorry!* There seems to be some uncertainly as to whether his birthday was May 25 or May 26, something that seems unusual for the age, and the social milieu into which he was born.** www.erenkrantz.com/Music/MilesDavisInterview.shtml*** www.wikipedia.com**** www.racematters.org/milesdavisobituary.htm

I’ve spent the week in black, or looking at black. No, no one’s died - this week was the culmination of our first 3-week performance block. It started off on Saturday in the Queen’s Hall for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra’s innovative and entertaining film scores performance. Having ranted in a previous blog about the Usher Hall’s acoustics, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the acoustics upstairs at the Queen’s Hall. I usually sit downstairs for folk concerts at the Queen’s Hall and it’s not an easy venue - all those pillars and the hard pews. The seats upstairs are still hard, but we had a great view of the orchestra and great sound.

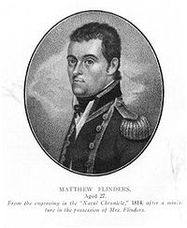

The concert included film scores by Takemitsu (lovely, I had never heard his music before and will be looking for more), Saint-Saëns (gorgeous), Shostakovic (energetic, stereotypic, comedic and compelling) and the world premiere of Gordon Kerry’s “Captain Flinders’ Musick” for flute and small orchestra. Despite my husband’s misgivings, (how well he remembers the last flute concert I dragged him to, that inscrutable Flutes of the World concert), the concert was one of the most delightful performances we have been to recently. Alison Mitchell’s flute playing was light, accurate and effervescent. Captain Flinders’ contained engaging musical figures, but might have benefitted from being longer, and perhaps in more movements, so that the melodies could have had more development.

A white cat crossed my path on my way to college on Wednesday for the Trad Band’s concert, and reappeared at my feet on Thursday on my way to the more formal classical performances. I wondered if that was a bad omen, as white lilies are a symbol of death in Japan. Having survived, I hope white’s other symbolism may be more applicable - the end of one “life” and the beginning of another.

Wednesday’s Trad Band concert was great fun, two sets with unusual arrangements that flew by in a flurry or even a scurry. I hope we get the chance to perform these again, but perhaps at a slightly slower and more comfortable speed - it’s really hard to get into a groove at warp speed!

For me, Thursday’s concert felt more relaxed. There is so much less performance pressure when the music is sitting in front of me. I’ve been surprised at how much I’ve enjoyed playing classical music in the concert band (oboe aka wooden flute) and string group (oboe aka english concertina). It’s been so companionable, sitting within a large group of other musicians, playing together. All of the octave jumps in the Handel have been great for my technique as has playing the wooden flute in the Holst Dflat section. Despite very little rehearsal time, the Shrek arrangement had a huge impact on the audience. We’re still singing “Who Let the Dogs Out” in our house, much to the consternation of the real dogs. The choir was great too, although I discovered how difficult it is to actually read the score when sandwiched in like a sardine - must learn the words before our next performance at the Usher Hall!

It’s been particularly interesting rehearsing for these performances. Both Neil Metcalfe and Laurie Crump bring a mindfulness to the musical and a clear vision for what they want to hear. I’ve learned more about phrasing from a one hour sectional with Neil than a lifetime of playing, and similarly from Laurie’s attention to the dynamic content of the Handel.

(Finally, thanks to my long-suffering husband for the title to this blog. I was going to call it “All Blacks” but thought that might be too politically incorrect. The credit is his, the errors are always all mine.)

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed